Burr–Hamilton Duel on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Burr–Hamilton duel took place in

The Burr–Hamilton duel is one of the most famous personal conflicts in American history. It was a pistol duel that arose from long-standing personal bitterness that developed between the two men over the course of several years. Tension rose with Hamilton's journalistic defamation of Burr's character during the 1804 New York gubernatorial election, 1804 New York gubernatorial race, in which Burr was a candidate.

The duel was fought at a time when the practice was being outlawed in the northern United States, and it had immense political ramifications. Burr survived the duel and was indicted for murder in both New York (state), New York and New Jersey, though these charges later were either dismissed or resulted in acquittal. The harsh criticism and animosity directed toward Burr following the duel brought an end to his political career. The Federalist Party was already weakened by the defeat of John Adams in the presidential election of 1800 and was further weakened by Hamilton's death.

The duel was the final skirmish of a long conflict between Democratic-Republican Party, Democratic-Republicans and Federalists. The conflict began in 1791 when Burr won a United States Senate seat from Philip Schuyler, Hamilton's father-in-law, who would have supported Federalist policies (Hamilton was the Secretary of the Treasury at the time). The Electoral College (United States), Electoral College then deadlocked in the election of 1800, during which Hamilton's maneuvering in the House of Representatives caused Thomas Jefferson to be named president and Burr vice president. At the time, the most votes resulted in an election win, while second place received the vice presidency. There were only proto-political parties at the time, as disdainfully noted in President Washington's Farewell Address, and no shared tickets.

Hamilton's animosity toward Burr was severe and well-documented in personal letters to his friend and compatriot James McHenry. The following quotation from one of these letters on January 4, 1801, exemplifies his bitterness:

The Burr–Hamilton duel is one of the most famous personal conflicts in American history. It was a pistol duel that arose from long-standing personal bitterness that developed between the two men over the course of several years. Tension rose with Hamilton's journalistic defamation of Burr's character during the 1804 New York gubernatorial election, 1804 New York gubernatorial race, in which Burr was a candidate.

The duel was fought at a time when the practice was being outlawed in the northern United States, and it had immense political ramifications. Burr survived the duel and was indicted for murder in both New York (state), New York and New Jersey, though these charges later were either dismissed or resulted in acquittal. The harsh criticism and animosity directed toward Burr following the duel brought an end to his political career. The Federalist Party was already weakened by the defeat of John Adams in the presidential election of 1800 and was further weakened by Hamilton's death.

The duel was the final skirmish of a long conflict between Democratic-Republican Party, Democratic-Republicans and Federalists. The conflict began in 1791 when Burr won a United States Senate seat from Philip Schuyler, Hamilton's father-in-law, who would have supported Federalist policies (Hamilton was the Secretary of the Treasury at the time). The Electoral College (United States), Electoral College then deadlocked in the election of 1800, during which Hamilton's maneuvering in the House of Representatives caused Thomas Jefferson to be named president and Burr vice president. At the time, the most votes resulted in an election win, while second place received the vice presidency. There were only proto-political parties at the time, as disdainfully noted in President Washington's Farewell Address, and no shared tickets.

Hamilton's animosity toward Burr was severe and well-documented in personal letters to his friend and compatriot James McHenry. The following quotation from one of these letters on January 4, 1801, exemplifies his bitterness:

It became clear that Jefferson would drop Burr from his ticket in the 1804_United_States_presidential_election, 1804 election, so the Vice President ran for the governorship of New York instead. He was backed by members of the Federalist Party and was under patronage of Tammany Hall in the 1804 New York gubernatorial election. Hamilton campaigned vigorously against Burr, causing him to lose to Morgan Lewis (governor), Morgan Lewis, a DeWitt Clinton, Clintonian Democratic-Republican endorsed by Hamilton.

Both men had been involved in duels in the past. Hamilton had been the second in several duels, although never the duelist himself, but he was involved in more than a dozen affairs of honor prior to his fatal encounter with Burr, including disputes with William Gordon (New Hampshire politician), William Gordon (1779), Aedanus Burke (1790), John Francis Mercer (1792–1793), James Nicholson (naval officer), James Nicholson (1795), James Monroe (1797), and Ebenezer Purdy and George Clinton (vice president), George Clinton (1804). He also served as a second to John Laurens in a 1779 duel with General Charles Lee (general), Charles Lee, and to legal client John Auldjo in a 1787 duel with William Pierce (politician), William Pierce. Hamilton also claimed that he had one previous honor dispute with Burr, while Burr stated that there were two.

Additionally, Hamilton's son Philip Hamilton, Philip was killed in a November 23, 1801, duel with George I. Eacker, initiated after Philip and his friend Richard Price engaged in "hooliganish" behavior in Eacker's box at the Park Theatre (Manhattan, New York). This was in response to a speech that Eacker had made on July 3, 1801, that was critical of Hamilton. Philip and his friend both challenged Eacker to duels when he called them "damned rascals". Price's duel (also at Weehawken) resulted in nothing more than four missed shots, and Hamilton advised his son to ''delope'' (throw away his shot). However, both Philip and Eacker stood shotless for a minute after the command "present", then Philip leveled his pistol, causing Eacker to fire, mortally wounding Philip and sending his shot awry.

It became clear that Jefferson would drop Burr from his ticket in the 1804_United_States_presidential_election, 1804 election, so the Vice President ran for the governorship of New York instead. He was backed by members of the Federalist Party and was under patronage of Tammany Hall in the 1804 New York gubernatorial election. Hamilton campaigned vigorously against Burr, causing him to lose to Morgan Lewis (governor), Morgan Lewis, a DeWitt Clinton, Clintonian Democratic-Republican endorsed by Hamilton.

Both men had been involved in duels in the past. Hamilton had been the second in several duels, although never the duelist himself, but he was involved in more than a dozen affairs of honor prior to his fatal encounter with Burr, including disputes with William Gordon (New Hampshire politician), William Gordon (1779), Aedanus Burke (1790), John Francis Mercer (1792–1793), James Nicholson (naval officer), James Nicholson (1795), James Monroe (1797), and Ebenezer Purdy and George Clinton (vice president), George Clinton (1804). He also served as a second to John Laurens in a 1779 duel with General Charles Lee (general), Charles Lee, and to legal client John Auldjo in a 1787 duel with William Pierce (politician), William Pierce. Hamilton also claimed that he had one previous honor dispute with Burr, while Burr stated that there were two.

Additionally, Hamilton's son Philip Hamilton, Philip was killed in a November 23, 1801, duel with George I. Eacker, initiated after Philip and his friend Richard Price engaged in "hooliganish" behavior in Eacker's box at the Park Theatre (Manhattan, New York). This was in response to a speech that Eacker had made on July 3, 1801, that was critical of Hamilton. Philip and his friend both challenged Eacker to duels when he called them "damned rascals". Price's duel (also at Weehawken) resulted in nothing more than four missed shots, and Hamilton advised his son to ''delope'' (throw away his shot). However, both Philip and Eacker stood shotless for a minute after the command "present", then Philip leveled his pistol, causing Eacker to fire, mortally wounding Philip and sending his shot awry.

In the early morning of July 11, 1804, Burr and Hamilton departed from Manhattan by separate boats and rowed across the

In the early morning of July 11, 1804, Burr and Hamilton departed from Manhattan by separate boats and rowed across the

Burr–Hamilton Duel

Teachinghistory.org

Accessed July 11, 2011. Dueling had been prohibited in both New York and New Jersey, but Hamilton and Burr agreed to go to Weehawken because New Jersey was not as aggressive as New York in prosecuting dueling participants. The same site was used for 18 known duels between 1700 and 1845, and it was not far from the site of the 1801 duel that killed Hamilton's eldest son Philip Hamilton. They also took steps to give all witnesses plausible deniability in an attempt to shield themselves from prosecution. For example, the pistols were transported to the island in a Portmanteau (luggage), portmanteau, enabling the rowers to say under oath that they had not seen any pistols. They also stood with their backs to the duelists. Burr, William Peter Van Ness (his second (duel), second), Matthew L. Davis, another man (often identified as John Swarthout), and the rowers all reached the site at 6:30 a.m., whereupon Swarthout and Van Ness started to clear the underbrush from the dueling ground. Hamilton, Judge Nathaniel Pendleton (his second), and Dr. David Hosack arrived a few minutes before seven. Lots were cast for the choice of position and which second should start the duel. Both were won by Hamilton's second, who chose the upper edge of the ledge for Hamilton, facing the city.Winfield, 1874, p. 219. However, Joseph Ellis claims that Hamilton had been challenged and therefore had the choice of both weapon and position. Under this account, Hamilton himself chose the upstream or north side position.Ellis, Joseph. Founding Brothers. p. 24 Some first-hand accounts of the duel agree that two shots were fired, but some say only Burr fired, and the seconds disagreed on the intervening time between them. It was common for both principals in a duel to deliberately miss or fire their shot into the ground to exemplify courage (a practice known as ''deloping''). The duel could then come to an end. Hamilton apparently fired a shot above Burr's head. Burr returned fire and hit Hamilton in the lower abdomen above the right hip.Winfield, 1874, pp. 219–220. The large-caliber lead ball ricocheted off Hamilton's third or second False ribs, false rib, fracturing it and causing considerable damage to his internal organs, particularly his liver and diaphragm, before lodging in his first or second lumbar vertebra. According to Pendleton's account, Hamilton collapsed almost immediately, dropping the pistol involuntarily, and Burr moved toward him in a speechless manner (which Pendleton deemed to be indicative of regret) before being hustled away behind an umbrella by Van Ness because Hosack and the rowers were already approaching. It is entirely uncertain which principal fired first, as both seconds' backs were to the duel in accordance with the pre-arranged regulations so that they could testify that they "saw no fire". After much research to determine the actual events of the duel, historian Joseph Ellis gives his best guess:

The pistols used in the duel belonged to Hamilton's brother-in-law John Barker Church, who was a business partner of both Hamilton and Burr. Later legend claimed that these pistols were the same ones used in a 1799 duel between Church and Burr in which neither man was injured.Alexander Hamilton, by Ron Chernow, p. 590 Burr, however, wrote in his memoirs that he supplied the pistols for his duel with Church, and that they belonged to him.

The Wogdon & Barton dueling pistols incorporated a wiktionary:hair-trigger, hair-trigger feature that could be set by the user. Hamilton was familiar with the weapons and would have been able to use the hair trigger. However, Pendleton asked him before the duel whether he would use the "hair-spring", and Hamilton reportedly replied, "Not this time."

Hamilton's son Philip Hamilton, Philip and George Eacker likely used the Church weapons in the 1801 duel in which Philip died, three years before the Burr–Hamilton duel. They were kept at Church's estate Belvidere (Belmont, New York), Belvidere until the late 19th century; See also: they were sold in 1930 to the Chase Manhattan Bank (now part of JP Morgan Chase), which traces its descent back to the Manhattan Company founded by Burr, and are on display in the bank's headquarters at 270 Park Avenue in New York City.

The pistols used in the duel belonged to Hamilton's brother-in-law John Barker Church, who was a business partner of both Hamilton and Burr. Later legend claimed that these pistols were the same ones used in a 1799 duel between Church and Burr in which neither man was injured.Alexander Hamilton, by Ron Chernow, p. 590 Burr, however, wrote in his memoirs that he supplied the pistols for his duel with Church, and that they belonged to him.

The Wogdon & Barton dueling pistols incorporated a wiktionary:hair-trigger, hair-trigger feature that could be set by the user. Hamilton was familiar with the weapons and would have been able to use the hair trigger. However, Pendleton asked him before the duel whether he would use the "hair-spring", and Hamilton reportedly replied, "Not this time."

Hamilton's son Philip Hamilton, Philip and George Eacker likely used the Church weapons in the 1801 duel in which Philip died, three years before the Burr–Hamilton duel. They were kept at Church's estate Belvidere (Belmont, New York), Belvidere until the late 19th century; See also: they were sold in 1930 to the Chase Manhattan Bank (now part of JP Morgan Chase), which traces its descent back to the Manhattan Company founded by Burr, and are on display in the bank's headquarters at 270 Park Avenue in New York City.

Image:AntiDuelingPamphletEliphaletNott1804.jpg, 1804 Anti-dueling sermon by an acquaintance of

Pistols at Weehawken

" Weehawken Historical Commission. * Chernow, Ron (2004). ''Alexander Hamilton''. The Penguin Press * Coleman, William (1804). ''A Collection of Facts and Documents, relative to the death of Major-General Alexander Hamilton''. New York. * Cooke, Syrett and Jean G, eds. (1960). ''Interview in Weehawken: The Burr–Hamilton Duel as Told in the Original Documents''. Middletown, Connecticut. * Cooper to Philip Schuyler. April 23, 1804. 26: 246. * Cooper, Charles D. (April 24, 1804). ''Albany Register''. * Davis, Matthew L. ''Memoirs of Aaron Burr'' (free ebook available from Project Gutenberg). * Demontreux, Willie (2004).

The Changing Face of the Hamilton Monument

" Weehawken Historical Commission. * Joseph Ellis, Ellis, Joseph J. (2000). ''Founding Brothers, Founding Brothers: The Revolutionary Generation.'' ''(Chapter One: The Duel)'', Alfred A. Knopf. New York. * Flagg, Thomas R. (2004).

An Investigation into the Location of the Weehawken Dueling Ground

" Weehawken Historical Commission. * Fleming, Thomas (1999). ''The Duel: Alexander Hamilton, Aaron Burr, and the Future of America''. New York: Perseus Books. * Frazier, Ian (February 16, 2004).

Route 3

" ''The New Yorker''. * Freeman, Joanne B. (1996). ''Dueling as Politics: Reinterpreting the Burr–Hamilton duel'', The William and Mary Quarterly, 3rd series, 53 (2): 289–318. * ''Georgia Republican & State Intelligencer'' (July 31, 1804) :File:18040731 General Hamilton is Dead - (Burr-Hamilton duel) Savannah Georgia Republican & State Intelligencer.jpg , General Hamilton is dead! Savannah, Georgia, U.S., July 31, 1804, p. 3. * Hamilton, Alexander. "Statement on Impending Duel with Aaron Burr," [June 28 – July 10], 26: 278. * Hamilton, Alexander. ''The Papers of Alexander Hamilton''. Harold C. Syrett, ed. 27 vols. New York: 1961–1987 * Lindsay, Merrill (1976)

"Pistols Shed Light on Famed Duel."

''Smithsonian'', VI (November): 94–98. * McGrath, Ben. May 31, 2004.

Reënactment: Burr vs. Hamilton

." ''The New Yorker''. * New York Evening Post. July 17, 1804.

Funeral Obsequies

" From the Collection of the New York Historical Society. * Ogden, Thomas H. (1979). "On Projective Identifications," in ''International Journal of Psychoanalysis'', 60, 357. Cf. Rogow, A Fatal Friendship, 327, note 29. * PBS. 1996.

American Experience: The Duel

''. Documentary transcript. * Reid, John (1898).

Where Hamilton Fell: The Exact Location of the Famous Duelling Ground

" Weehawken Historical Commission. * * Sabine, Lorenzo. ''Notes on Duels and Duelling''. Boston. * Van Ness, William P. (1804). ''A Correct Statement of the Late Melancholy Affair of Honor, Between General Hamilton and Col. Burr. New York. * ''William P. Ness vs. The People.'' January 1805. Duel papers, William P. Ness papers, New York Historical Society. * * Winfield, Charles H. (1874). ''History of the County of Hudson, New Jersey from Its Earliest Settlement to the Present Time''. New York: Kennard and Hay. Chapter 8,

Duels

" pp. 200–231.

– Official PBS Hamilton-Burr Duel Documentary site

Duel 2004

– A site dedicated to the 200th anniversary of the duel. {{DEFAULTSORT:Burr-Hamilton Duel 1804 in New Jersey 1804 in the United States 1935 sculptures Alexander Hamilton, Duel Dueling Monuments and memorials in New Jersey Political history of the United States Political violence in the United States Weehawken, New Jersey July 1804 events

Weehawken, New Jersey

Weehawken is a Township (New Jersey), township in the North Hudson, New Jersey, northern part of Hudson County, New Jersey, Hudson County, in the U.S. state of New Jersey. It is located largely on the Hudson Palisades overlooking the North River ...

, between Aaron Burr

Aaron Burr Jr. (February 6, 1756 – September 14, 1836) was an American politician and lawyer who served as the third vice president of the United States from 1801 to 1805. Burr's legacy is defined by his famous personal conflict with Alexand ...

, the Vice President of the United States

The vice president of the United States (VPOTUS) is the second-highest officer in the executive branch of the U.S. federal government, after the president of the United States, and ranks first in the presidential line of succession. The vice ...

, and Alexander Hamilton

Alexander Hamilton (January 11, 1755 or 1757July 12, 1804) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first United States secretary of the treasury from 1789 to 1795.

Born out of wedlock in Charlest ...

, the first and former Secretary of the Treasury

The United States secretary of the treasury is the head of the United States Department of the Treasury, and is the chief financial officer of the federal government of the United States. The secretary of the treasury serves as the principal a ...

, on the morning of July 11, 1804. The duel

A duel is an arranged engagement in combat between two people, with matched weapons, in accordance with agreed-upon Code duello, rules.

During the 17th and 18th centuries (and earlier), duels were mostly single combats fought with swords (the r ...

was the culmination of a bitter rivalry that had developed between both men, who had become high-profile politicians in post-colonial America. In the duel, Burr fatally shot Hamilton, while Hamilton fired into a tree branch above and behind Burr's head. Hamilton was taken back across the Hudson River

The Hudson River is a river that flows from north to south primarily through eastern New York. It originates in the Adirondack Mountains of Upstate New York and flows southward through the Hudson Valley to the New York Harbor between N ...

, and he died the following day in New York City, New York.

The death of Hamilton led to the permanent weakening of the Federalist Party and its demise in American domestic politics. It also effectively ended the political career of Burr, who was vilified for shooting Hamilton; he never held another high office after his tenure of vice president ended in 1805.

Background

The Burr–Hamilton duel is one of the most famous personal conflicts in American history. It was a pistol duel that arose from long-standing personal bitterness that developed between the two men over the course of several years. Tension rose with Hamilton's journalistic defamation of Burr's character during the 1804 New York gubernatorial election, 1804 New York gubernatorial race, in which Burr was a candidate.

The duel was fought at a time when the practice was being outlawed in the northern United States, and it had immense political ramifications. Burr survived the duel and was indicted for murder in both New York (state), New York and New Jersey, though these charges later were either dismissed or resulted in acquittal. The harsh criticism and animosity directed toward Burr following the duel brought an end to his political career. The Federalist Party was already weakened by the defeat of John Adams in the presidential election of 1800 and was further weakened by Hamilton's death.

The duel was the final skirmish of a long conflict between Democratic-Republican Party, Democratic-Republicans and Federalists. The conflict began in 1791 when Burr won a United States Senate seat from Philip Schuyler, Hamilton's father-in-law, who would have supported Federalist policies (Hamilton was the Secretary of the Treasury at the time). The Electoral College (United States), Electoral College then deadlocked in the election of 1800, during which Hamilton's maneuvering in the House of Representatives caused Thomas Jefferson to be named president and Burr vice president. At the time, the most votes resulted in an election win, while second place received the vice presidency. There were only proto-political parties at the time, as disdainfully noted in President Washington's Farewell Address, and no shared tickets.

Hamilton's animosity toward Burr was severe and well-documented in personal letters to his friend and compatriot James McHenry. The following quotation from one of these letters on January 4, 1801, exemplifies his bitterness:

The Burr–Hamilton duel is one of the most famous personal conflicts in American history. It was a pistol duel that arose from long-standing personal bitterness that developed between the two men over the course of several years. Tension rose with Hamilton's journalistic defamation of Burr's character during the 1804 New York gubernatorial election, 1804 New York gubernatorial race, in which Burr was a candidate.

The duel was fought at a time when the practice was being outlawed in the northern United States, and it had immense political ramifications. Burr survived the duel and was indicted for murder in both New York (state), New York and New Jersey, though these charges later were either dismissed or resulted in acquittal. The harsh criticism and animosity directed toward Burr following the duel brought an end to his political career. The Federalist Party was already weakened by the defeat of John Adams in the presidential election of 1800 and was further weakened by Hamilton's death.

The duel was the final skirmish of a long conflict between Democratic-Republican Party, Democratic-Republicans and Federalists. The conflict began in 1791 when Burr won a United States Senate seat from Philip Schuyler, Hamilton's father-in-law, who would have supported Federalist policies (Hamilton was the Secretary of the Treasury at the time). The Electoral College (United States), Electoral College then deadlocked in the election of 1800, during which Hamilton's maneuvering in the House of Representatives caused Thomas Jefferson to be named president and Burr vice president. At the time, the most votes resulted in an election win, while second place received the vice presidency. There were only proto-political parties at the time, as disdainfully noted in President Washington's Farewell Address, and no shared tickets.

Hamilton's animosity toward Burr was severe and well-documented in personal letters to his friend and compatriot James McHenry. The following quotation from one of these letters on January 4, 1801, exemplifies his bitterness:

"Nothing has given me so much chagrin as the Intelligence that the Federal party were thinking seriously of supporting Mr. Burr for president. I should consider the execution of the plan as wikt:devote#Verb, devoting the country and signing their own death warrant. Mr. Burr will probably make stipulations, but he will laugh in his sleeve while he makes them and will break them the first moment it may serve his purpose."Bernard C. Steiner and James McHenry,Hamilton details the many charges that he has against Burr in a more extensive letter written shortly afterward, calling him a "profligate, a voluptuary in the extreme", accusing him of corruptly serving the interests of the Holland Land Company while a member of the legislature, criticizing his military commission and accusing him of resigning it under false pretenses, and many more serious accusations.

The life and correspondence of James McHenry

' (Cleveland: Burrows Brothers Co., 1907).

It became clear that Jefferson would drop Burr from his ticket in the 1804_United_States_presidential_election, 1804 election, so the Vice President ran for the governorship of New York instead. He was backed by members of the Federalist Party and was under patronage of Tammany Hall in the 1804 New York gubernatorial election. Hamilton campaigned vigorously against Burr, causing him to lose to Morgan Lewis (governor), Morgan Lewis, a DeWitt Clinton, Clintonian Democratic-Republican endorsed by Hamilton.

Both men had been involved in duels in the past. Hamilton had been the second in several duels, although never the duelist himself, but he was involved in more than a dozen affairs of honor prior to his fatal encounter with Burr, including disputes with William Gordon (New Hampshire politician), William Gordon (1779), Aedanus Burke (1790), John Francis Mercer (1792–1793), James Nicholson (naval officer), James Nicholson (1795), James Monroe (1797), and Ebenezer Purdy and George Clinton (vice president), George Clinton (1804). He also served as a second to John Laurens in a 1779 duel with General Charles Lee (general), Charles Lee, and to legal client John Auldjo in a 1787 duel with William Pierce (politician), William Pierce. Hamilton also claimed that he had one previous honor dispute with Burr, while Burr stated that there were two.

Additionally, Hamilton's son Philip Hamilton, Philip was killed in a November 23, 1801, duel with George I. Eacker, initiated after Philip and his friend Richard Price engaged in "hooliganish" behavior in Eacker's box at the Park Theatre (Manhattan, New York). This was in response to a speech that Eacker had made on July 3, 1801, that was critical of Hamilton. Philip and his friend both challenged Eacker to duels when he called them "damned rascals". Price's duel (also at Weehawken) resulted in nothing more than four missed shots, and Hamilton advised his son to ''delope'' (throw away his shot). However, both Philip and Eacker stood shotless for a minute after the command "present", then Philip leveled his pistol, causing Eacker to fire, mortally wounding Philip and sending his shot awry.

It became clear that Jefferson would drop Burr from his ticket in the 1804_United_States_presidential_election, 1804 election, so the Vice President ran for the governorship of New York instead. He was backed by members of the Federalist Party and was under patronage of Tammany Hall in the 1804 New York gubernatorial election. Hamilton campaigned vigorously against Burr, causing him to lose to Morgan Lewis (governor), Morgan Lewis, a DeWitt Clinton, Clintonian Democratic-Republican endorsed by Hamilton.

Both men had been involved in duels in the past. Hamilton had been the second in several duels, although never the duelist himself, but he was involved in more than a dozen affairs of honor prior to his fatal encounter with Burr, including disputes with William Gordon (New Hampshire politician), William Gordon (1779), Aedanus Burke (1790), John Francis Mercer (1792–1793), James Nicholson (naval officer), James Nicholson (1795), James Monroe (1797), and Ebenezer Purdy and George Clinton (vice president), George Clinton (1804). He also served as a second to John Laurens in a 1779 duel with General Charles Lee (general), Charles Lee, and to legal client John Auldjo in a 1787 duel with William Pierce (politician), William Pierce. Hamilton also claimed that he had one previous honor dispute with Burr, while Burr stated that there were two.

Additionally, Hamilton's son Philip Hamilton, Philip was killed in a November 23, 1801, duel with George I. Eacker, initiated after Philip and his friend Richard Price engaged in "hooliganish" behavior in Eacker's box at the Park Theatre (Manhattan, New York). This was in response to a speech that Eacker had made on July 3, 1801, that was critical of Hamilton. Philip and his friend both challenged Eacker to duels when he called them "damned rascals". Price's duel (also at Weehawken) resulted in nothing more than four missed shots, and Hamilton advised his son to ''delope'' (throw away his shot). However, both Philip and Eacker stood shotless for a minute after the command "present", then Philip leveled his pistol, causing Eacker to fire, mortally wounding Philip and sending his shot awry.

Election of 1800

Burr and Hamilton first came into public opposition during the United States presidential election of 1800. Burr ran for president on the Democratic-Republican ticket, along with Thomas Jefferson, against President John Adams (the Federalist incumbent) and his vice presidential running mate Charles Cotesworth Pinckney, Charles C. Pinckney. Electoral College rules at the time gave each elector two votes for president. The candidate who received the second most votes became vice president. The Democratic-Republican Party planned to have 72 of their 73 electors vote for both Jefferson and Burr, with the remaining elector voting only for Jefferson. The electors failed to execute this plan, so Burr and Jefferson were tied with 73 votes each. The Constitution stipulated that if two candidates with an Electoral College majority were tied, the election would be moved to the House of Representatives—which was controlled by the Federalists, at this point, many of whom were loath to vote for Jefferson. Although Hamilton had a long-standing rivalry with Jefferson stemming from their tenure as members of George Washington's cabinet, he regarded Burr as far more dangerous and used all his influence to ensure Jefferson's election. On the 36th ballot, the House of Representatives gave Jefferson the presidency, with Burr becoming vice president.Charles Cooper's letter

On April 24, 1804, the ''Albany Register'' published a letter opposing Burr's gubernatorial candidacy which was originally sent from Charles D. Cooper to Hamilton's father-in-law, former senator Philip Schuyler. It made reference to a previous statement by Cooper: "General Hamilton and Judge Kent have declared in substance that they looked upon Mr. Burr to be a dangerous man, and one who ought not be trusted with the reins of government." Cooper went on to emphasize that he could describe in detail "a still more despicable opinion which General Hamilton has expressed of Mr. Burr" at a political dinner. Burr responded in a letter delivered by William P. Van Ness which pointed particularly to the phrase "more despicable" and demanded "a prompt and unqualified acknowledgment or denial of the use of any expression which would warrant the assertion of Dr. Cooper." Hamilton's verbose reply on June 20, 1804, indicated that he could not be held responsible for Cooper's interpretation of his words (yet he did not fault that interpretation), concluding that he would "abide the consequences" should Burr remain unsatisfied. A recurring theme in their correspondence is that Burr seeks avowal or disavowal of ''anything'' that could justify Cooper's characterization, while Hamilton protests that there are no ''specifics''. Burr replied on June 21, 1804, also delivered by Van Ness, stating that "political opposition can never absolve gentlemen from the necessity of a rigid adherence to the laws of honor and the rules of decorum". Hamilton replied that he had "no other answer to give than that which has already been given". This letter was delivered to Nathaniel Pendleton on June 22 but did not reach Burr until June 25. The delay was due to negotiation between Pendleton and Van Ness in which Pendleton submitted the following paper: Eventually, Burr issued a formal challenge and Hamilton accepted. Many historians have considered the causes of the duel to be flimsy and have thus characterized Hamilton as "suicidal", Burr as "malicious and murderous", or both. Thomas Fleming offers the theory that Burr may have been attempting to recover his honor by challenging Hamilton, whom he considered to be the only gentleman among his detractors, in response to the slanderous attacks against his character published during the 1804 gubernatorial campaign. Hamilton's reasons for not engaging in a duel included his roles as father and husband, putting his creditors at risk, and placing his family's welfare in jeopardy, but he felt that it would be impossible to avoid a duel because he had made attacks on Burr that he was unable to recant, and because of Burr's behavior prior to the duel. He attempted to reconcile his moral and religious reasons and the codes of honor and politics. Joanne Freeman speculates that Hamilton intended to accept the duel and Deloping, throw away his shot in order to satisfy his moral and political codes.Duel

In the early morning of July 11, 1804, Burr and Hamilton departed from Manhattan by separate boats and rowed across the

In the early morning of July 11, 1804, Burr and Hamilton departed from Manhattan by separate boats and rowed across the Hudson River

The Hudson River is a river that flows from north to south primarily through eastern New York. It originates in the Adirondack Mountains of Upstate New York and flows southward through the Hudson Valley to the New York Harbor between N ...

to a spot known as the Heights of Weehawken, New Jersey

Weehawken is a Township (New Jersey), township in the North Hudson, New Jersey, northern part of Hudson County, New Jersey, Hudson County, in the U.S. state of New Jersey. It is located largely on the Hudson Palisades overlooking the North River ...

, a popular dueling ground below the towering cliffs of the New Jersey Palisades.Buescher, John.Burr–Hamilton Duel

Teachinghistory.org

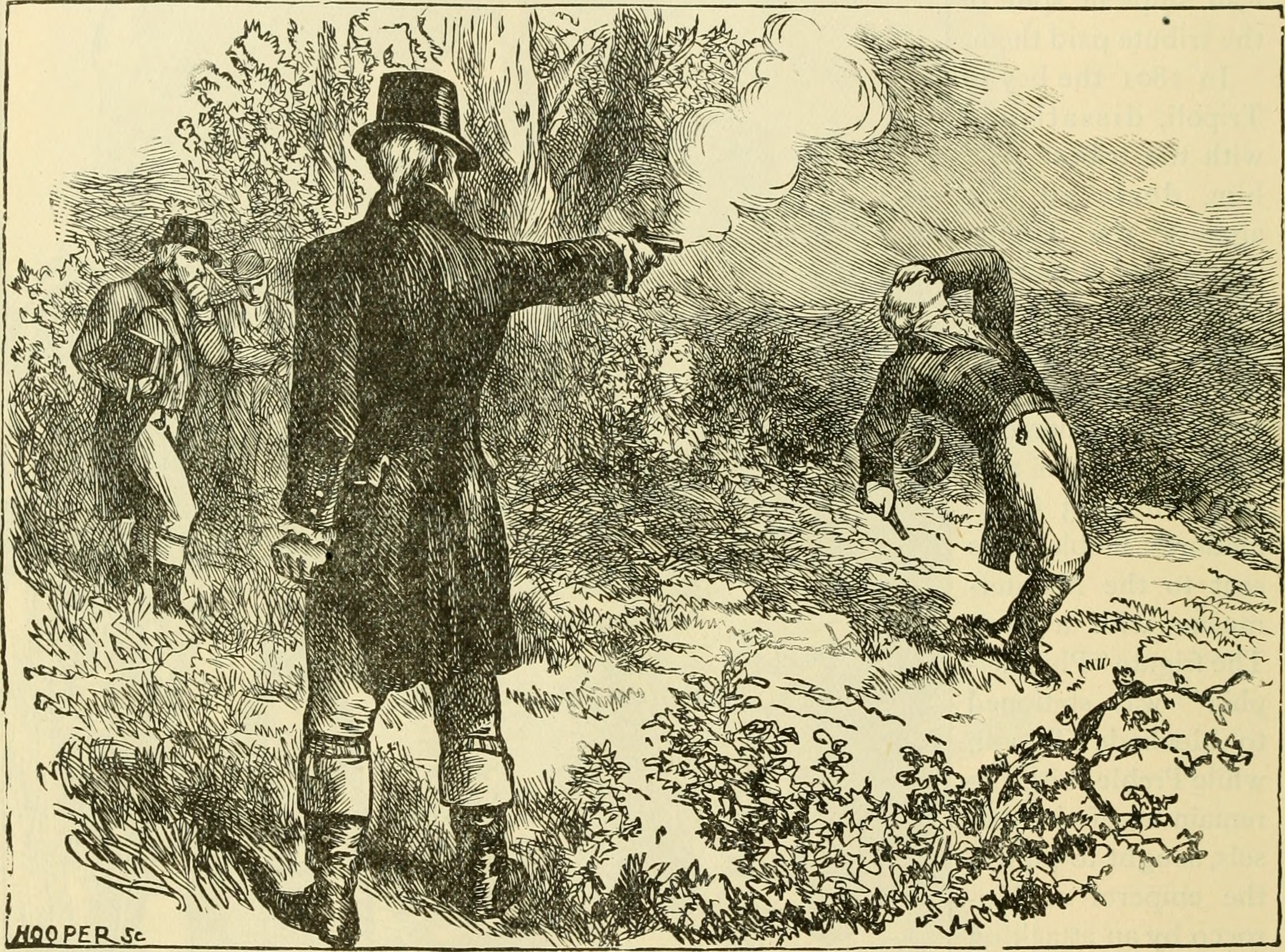

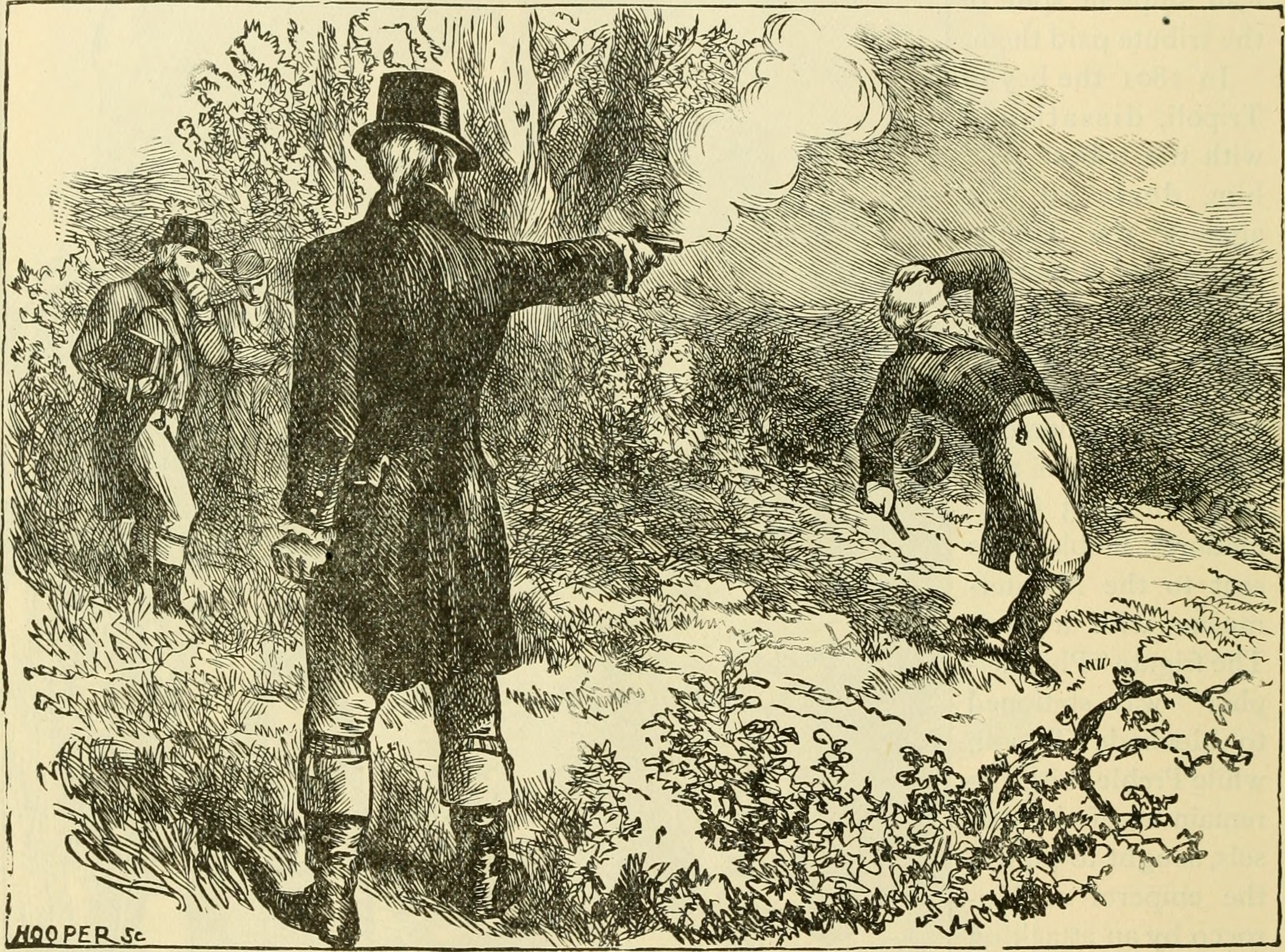

Accessed July 11, 2011. Dueling had been prohibited in both New York and New Jersey, but Hamilton and Burr agreed to go to Weehawken because New Jersey was not as aggressive as New York in prosecuting dueling participants. The same site was used for 18 known duels between 1700 and 1845, and it was not far from the site of the 1801 duel that killed Hamilton's eldest son Philip Hamilton. They also took steps to give all witnesses plausible deniability in an attempt to shield themselves from prosecution. For example, the pistols were transported to the island in a Portmanteau (luggage), portmanteau, enabling the rowers to say under oath that they had not seen any pistols. They also stood with their backs to the duelists. Burr, William Peter Van Ness (his second (duel), second), Matthew L. Davis, another man (often identified as John Swarthout), and the rowers all reached the site at 6:30 a.m., whereupon Swarthout and Van Ness started to clear the underbrush from the dueling ground. Hamilton, Judge Nathaniel Pendleton (his second), and Dr. David Hosack arrived a few minutes before seven. Lots were cast for the choice of position and which second should start the duel. Both were won by Hamilton's second, who chose the upper edge of the ledge for Hamilton, facing the city.Winfield, 1874, p. 219. However, Joseph Ellis claims that Hamilton had been challenged and therefore had the choice of both weapon and position. Under this account, Hamilton himself chose the upstream or north side position.Ellis, Joseph. Founding Brothers. p. 24 Some first-hand accounts of the duel agree that two shots were fired, but some say only Burr fired, and the seconds disagreed on the intervening time between them. It was common for both principals in a duel to deliberately miss or fire their shot into the ground to exemplify courage (a practice known as ''deloping''). The duel could then come to an end. Hamilton apparently fired a shot above Burr's head. Burr returned fire and hit Hamilton in the lower abdomen above the right hip.Winfield, 1874, pp. 219–220. The large-caliber lead ball ricocheted off Hamilton's third or second False ribs, false rib, fracturing it and causing considerable damage to his internal organs, particularly his liver and diaphragm, before lodging in his first or second lumbar vertebra. According to Pendleton's account, Hamilton collapsed almost immediately, dropping the pistol involuntarily, and Burr moved toward him in a speechless manner (which Pendleton deemed to be indicative of regret) before being hustled away behind an umbrella by Van Ness because Hosack and the rowers were already approaching. It is entirely uncertain which principal fired first, as both seconds' backs were to the duel in accordance with the pre-arranged regulations so that they could testify that they "saw no fire". After much research to determine the actual events of the duel, historian Joseph Ellis gives his best guess:

David Hosack's account

Hosack wrote his account on August 17, about one month after the duel had taken place. He testified that he had only seen Hamilton and the two seconds disappear "into the wood", heard two shots, and rushed to find a wounded Hamilton. He also testified that he had not seen Burr, who had been hidden behind an umbrella by Van Ness. He gives a very clear picture of the events in a letter to William Coleman (editor), William Coleman: Hosack goes on to say that Hamilton had revived after a few minutes, either from the hartshorn or fresh air. He finishes his letter:Statement to the press

Pendleton and Van Ness issued a press statement about the events of the duel which pointed out the agreed-upon dueling rules and events that transpired. It stated that both participants were free to open fire once they had been given the order to present. After first fire had been given, the opponent's second would count to three, whereupon the opponent would fire or sacrifice his shot. Pendleton and Van Ness disagree as to who fired the first shot, but they concur that both men had fired "within a few seconds of each other" (as they must have; neither Pendleton nor Van Ness mentions counting down). In Pendleton's amended version of the statement, he and a friend went to the site of the duel the day after Hamilton's death to discover where Hamilton's shot went. The statement reads:They ascertained that the ball passed through the limb of a cedar tree, at an elevation of about twelve feet and a half, perpendicularly from the ground, between thirteen and fourteen feet from the mark on which General Hamilton stood, and about four feet wide of the direct line between him and Col. Burr, on the right side; he having fallen on the left.Nathaniel Pendleton's Amended Version of His and William P. Ness's Statement of July 11, 1804.

Hamilton's intentions

Hamilton wrote a letter before the duel titled ''Statement on Impending Duel with Aaron Burr'' in which he stated that he was "strongly opposed to the practice of dueling" for both religious and practical reasons. "I have resolved," it continued, "if our interview is conducted in the usual manner, and it pleases God to give me the opportunity, to reserve and throw away my first fire, and I have thoughts even of reserving my second fire." Hamilton regained consciousness after being shot and told Dr. Hosack that his gun was still loaded and that "Pendleton knows I did not mean to fire at him." This is evidence for the theory that Hamilton intended not to fire, honoring his pre-duel pledge, and only fired accidentally upon being hit. Such an intention would have violated the protocol of the ''code duello'' and, when Burr learned of it, he responded: "Contemptible, if true." Hamilton could have thrown away his shot by firing into the ground, thus possibly signaling Burr of his purpose. Modern historians have debated to what extent Hamilton's statements and letter represent his true beliefs, and how much of this was a deliberate attempt to permanently ruin Burr if Hamilton were killed. An example of this may be seen in what one historian has considered to be deliberate attempts to provoke Burr on the dueling ground:Burr's intentions

There is evidence that Burr intended to kill Hamilton. The afternoon after the duel, he was quoted as saying that he would have shot Hamilton in the heart had his vision not been impaired by the morning mist. English philosopher Jeremy Bentham met with Burr in England in 1808, four years after the duel, and Burr claimed to have been certain of his ability to kill Hamilton. Bentham concluded that Burr was "little better than a murderer." There is also evidence in Burr's defense. Had Hamilton apologized for his "more despicable opinion of Mr. Burr", all would have been forgotten. However, the code duello required that injuries which needed an explanation or apology must be specifically stated. Burr's accusation was so unspecific that it could have referred to anything that Hamilton had said over 15 years of political rivalry. Despite this, Burr insisted on an answer. Burr knew of Hamilton's public opposition to his presidential run in 1800. Hamilton made confidential statements against him, such as those enumerated in his letter to Supreme Court Justice John Rutledge. In the attachment to that letter, Hamilton argued against Burr's character on numerous scores: he suspected Burr "on strong grounds of having corruptly served the views of the Holland Company;" "his very friends do not insist on his integrity"; "he will court and employ able and daring scoundrels;" he seeks "Supreme power in his own person" and "will in all likelihood attempt a usurpation," and so forth.Pistols

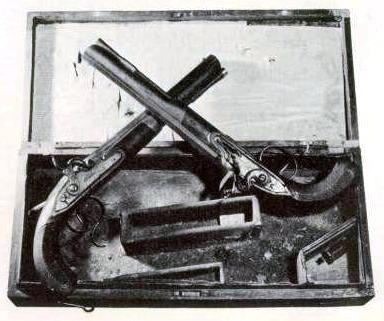

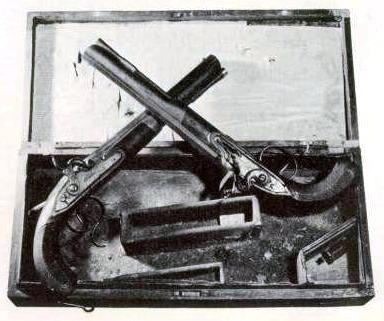

The pistols used in the duel belonged to Hamilton's brother-in-law John Barker Church, who was a business partner of both Hamilton and Burr. Later legend claimed that these pistols were the same ones used in a 1799 duel between Church and Burr in which neither man was injured.Alexander Hamilton, by Ron Chernow, p. 590 Burr, however, wrote in his memoirs that he supplied the pistols for his duel with Church, and that they belonged to him.

The Wogdon & Barton dueling pistols incorporated a wiktionary:hair-trigger, hair-trigger feature that could be set by the user. Hamilton was familiar with the weapons and would have been able to use the hair trigger. However, Pendleton asked him before the duel whether he would use the "hair-spring", and Hamilton reportedly replied, "Not this time."

Hamilton's son Philip Hamilton, Philip and George Eacker likely used the Church weapons in the 1801 duel in which Philip died, three years before the Burr–Hamilton duel. They were kept at Church's estate Belvidere (Belmont, New York), Belvidere until the late 19th century; See also: they were sold in 1930 to the Chase Manhattan Bank (now part of JP Morgan Chase), which traces its descent back to the Manhattan Company founded by Burr, and are on display in the bank's headquarters at 270 Park Avenue in New York City.

The pistols used in the duel belonged to Hamilton's brother-in-law John Barker Church, who was a business partner of both Hamilton and Burr. Later legend claimed that these pistols were the same ones used in a 1799 duel between Church and Burr in which neither man was injured.Alexander Hamilton, by Ron Chernow, p. 590 Burr, however, wrote in his memoirs that he supplied the pistols for his duel with Church, and that they belonged to him.

The Wogdon & Barton dueling pistols incorporated a wiktionary:hair-trigger, hair-trigger feature that could be set by the user. Hamilton was familiar with the weapons and would have been able to use the hair trigger. However, Pendleton asked him before the duel whether he would use the "hair-spring", and Hamilton reportedly replied, "Not this time."

Hamilton's son Philip Hamilton, Philip and George Eacker likely used the Church weapons in the 1801 duel in which Philip died, three years before the Burr–Hamilton duel. They were kept at Church's estate Belvidere (Belmont, New York), Belvidere until the late 19th century; See also: they were sold in 1930 to the Chase Manhattan Bank (now part of JP Morgan Chase), which traces its descent back to the Manhattan Company founded by Burr, and are on display in the bank's headquarters at 270 Park Avenue in New York City.

Aftermath

After being attended by Hosack, the mortally wounded Hamilton was taken to the home of William Bayard Jr. in New York, where he received communion from Bishop Benjamin Moore (bishop), Benjamin Moore. He died the next day after seeing his wife Elizabeth Schuyler Hamilton, Elizabeth and their children, in the presence of more than 20 friends and family members; he was buried in the Trinity Churchyard Cemetery in Manhattan. (Hamilton was an Episcopalian at the time of his death.) Burr was charged with murder in New York and New Jersey, but neither charge reached trial. In Bergen County, New Jersey, a grand jury indicted him for murder in November 1804, but the New Jersey Supreme Court quashed it on a motion from Colonel Ogden. Burr fled to St. Simons, Georgia, St. Simons Island, Georgia, and stayed at the plantation of Pierce Butler, but he soon returned to Washington, D.C. to complete his term as vice president. He presided over the impeachment trial of Samuel Chase "with the dignity and impartiality of an angel, but with the rigor of a devil", according to a Washington newspaper. Burr's heartfelt farewell speech to the Senate in March 1805 moved some of his harshest critics to tears.Memorials and monuments

The first memorial to the duel was constructed in 1806 by the Saint Andrew's Society of the State of New York of which Hamilton was a member. A 14-foot marble cenotaph was constructed where Hamilton was believed to have fallen, consisting of an obelisk topped by a flaming urn and a plaque with a quotation from Horace, the whole structure surrounded by an iron fence. Duels continued to be fought at the site and the marble was slowly vandalized and removed for souvenirs, with nothing remaining by 1820. The memorial's plaque survived, however, turning up in a junk store and finding its way to the New-York Historical Society in Manhattan where it still resides. From 1820 to 1857, the site was marked by two stones with the names Hamilton and Burr placed where they were thought to have stood during the duel, but a road was built through the site in 1858 from Hoboken, New Jersey, to Fort Lee, New Jersey; all that remained of those memorials was an inscription on a boulder where Hamilton was thought to have rested after the duel, but there are no primary accounts which confirm the boulder anecdote. Railroad tracks were laid directly through the site in 1870, and the boulder was hauled to the top of the Palisades where it remains today. An iron fence was built around it in 1874, supplemented by a bust of Hamilton and a plaque. The bust was thrown over the cliff on October 14, 1934, by vandals and the head was never recovered; a new bust was installed on July 12, 1935. The plaque was stolen by vandals in the 1980s and an abbreviated version of the text was inscribed on the indentation left in the boulder, which remained until the 1990s when a granite pedestal was added in front of the boulder and the bust was moved to the top of the pedestal. New markers were added on July 11, 2004, the 200th anniversary of the duel.Anti-dueling movement in New York state

In the months and years following the duel, a movement started to end the practice. Eliphalet Nott, the pastor at an Albany church attended by Hamilton's father-in-law, Philip Schuyler, gave a sermon that was soon reprinted, "iarchive:discourseoccasio00nott, A Discourse, Delivered in the North Dutch Church, in the City of Albany, Occasioned by the Ever to be Lamented Death of General Alexander Hamilton, July 29, 1804". In 1806, Lyman Beecher delivered an anti-dueling sermon, later reprinted in 1809 by the Anti-Dueling Association of New York. The covers and some pages of both pamphlets:Alexander Hamilton

Alexander Hamilton (January 11, 1755 or 1757July 12, 1804) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first United States secretary of the treasury from 1789 to 1795.

Born out of wedlock in Charlest ...

Image:EliphaletNottSermonDeathOfAlexanderHamiltonPartialText1809.jpg, Opening text of 1804 sermon

Image:TheRemedyForDuelingSermonLymanBeecherPamphlet1809.jpg, Anti-Dueling Association of New York pamphlet, ''Remedy'', 1809

Image:AntiDuelingAssocOfNYResolutions1809.jpg, Resolutions, Anti-Dueling Association of N.Y., from ''Remedy'' pamphlet, 1809

Image:AntiDuellingAssocOfNYAddressToNY1809.jpg, Address to the electorate, from ''Remedy'' pamphlet

In popular culture

The rules of dueling researched by historian Joanne B. Freeman provided inspiration for the song "Ten Duel Commandments" in the Broadway musical ''Hamilton (musical), Hamilton''. The songs "Alexander Hamilton (song), Alexander Hamilton", "Your Obedient Servant (song), Your Obedient Servant", and "The World Was Wide Enough" also refer to the duel, the very latter depicting the duel as it happened. The musical compresses the timeline for Burr and Hamilton's grievance, depicting Burr's challenge as a result of Hamilton's endorsement of Jefferson rather than the gubernatorial election. In ''Hamilton'', the penultimate duel scene depicts a resolved Hamilton who intentionally aims his pistol at the sky and a regretful Burr who realizes this too late and has already fired his shot. Descendants of Burr and Hamilton held a re-enactment of the duel near the Hudson River for the duel's bicentennial in 2004. Douglas Hamilton, fifth great-grandson of Alexander Hamilton, faced Antonio Burr, a descendant of Aaron Burr's cousin. More than 1,000 people attended it, including an estimated 60 descendants of Hamilton and 40 members of the Aaron Burr Association. The Alexander Hamilton Awareness Society has been hosting the Celebrate Hamilton program since 2012 to commemorate the Burr–Hamilton Duel and Alexander Hamilton's life and legacy. In his historical novel Burr (novel), ''Burr'' (1973), author Gore Vidal recreates an elderly Aaron Burr visiting the dueling ground in Weehawken. Burr begins to reflect, for the benefit of the novel's protagonist, upon what precipitated the duel, and then, to the unease of his one person audience, acts out the duel itself. The chapter concludes with Burr describing the personal, public, and political consequences he endures in the duel's aftermath.See also

* Dick Cheney hunting accident * List of feuds in the United StatesNotes

References

* ''The Adams Centinel'' (July 25, 1804) :File:18040725 Mourn, Oh Columbia - (Burr-Hamilton duel) The Adams Centinel.jpg , "Mourn, Oh Columbia! Thy Hamilton is gone to that 'bourn from whence no traveler returns'", Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, U.S., p. 3. * Berg, Al and Sherman, Lauren (2004).Pistols at Weehawken

" Weehawken Historical Commission. * Chernow, Ron (2004). ''Alexander Hamilton''. The Penguin Press * Coleman, William (1804). ''A Collection of Facts and Documents, relative to the death of Major-General Alexander Hamilton''. New York. * Cooke, Syrett and Jean G, eds. (1960). ''Interview in Weehawken: The Burr–Hamilton Duel as Told in the Original Documents''. Middletown, Connecticut. * Cooper to Philip Schuyler. April 23, 1804. 26: 246. * Cooper, Charles D. (April 24, 1804). ''Albany Register''. * Davis, Matthew L. ''Memoirs of Aaron Burr'' (free ebook available from Project Gutenberg). * Demontreux, Willie (2004).

The Changing Face of the Hamilton Monument

" Weehawken Historical Commission. * Joseph Ellis, Ellis, Joseph J. (2000). ''Founding Brothers, Founding Brothers: The Revolutionary Generation.'' ''(Chapter One: The Duel)'', Alfred A. Knopf. New York. * Flagg, Thomas R. (2004).

An Investigation into the Location of the Weehawken Dueling Ground

" Weehawken Historical Commission. * Fleming, Thomas (1999). ''The Duel: Alexander Hamilton, Aaron Burr, and the Future of America''. New York: Perseus Books. * Frazier, Ian (February 16, 2004).

Route 3

" ''The New Yorker''. * Freeman, Joanne B. (1996). ''Dueling as Politics: Reinterpreting the Burr–Hamilton duel'', The William and Mary Quarterly, 3rd series, 53 (2): 289–318. * ''Georgia Republican & State Intelligencer'' (July 31, 1804) :File:18040731 General Hamilton is Dead - (Burr-Hamilton duel) Savannah Georgia Republican & State Intelligencer.jpg , General Hamilton is dead! Savannah, Georgia, U.S., July 31, 1804, p. 3. * Hamilton, Alexander. "Statement on Impending Duel with Aaron Burr," [June 28 – July 10], 26: 278. * Hamilton, Alexander. ''The Papers of Alexander Hamilton''. Harold C. Syrett, ed. 27 vols. New York: 1961–1987 * Lindsay, Merrill (1976)

"Pistols Shed Light on Famed Duel."

''Smithsonian'', VI (November): 94–98. * McGrath, Ben. May 31, 2004.

Reënactment: Burr vs. Hamilton

." ''The New Yorker''. * New York Evening Post. July 17, 1804.

Funeral Obsequies

" From the Collection of the New York Historical Society. * Ogden, Thomas H. (1979). "On Projective Identifications," in ''International Journal of Psychoanalysis'', 60, 357. Cf. Rogow, A Fatal Friendship, 327, note 29. * PBS. 1996.

American Experience: The Duel

''. Documentary transcript. * Reid, John (1898).

Where Hamilton Fell: The Exact Location of the Famous Duelling Ground

" Weehawken Historical Commission. * * Sabine, Lorenzo. ''Notes on Duels and Duelling''. Boston. * Van Ness, William P. (1804). ''A Correct Statement of the Late Melancholy Affair of Honor, Between General Hamilton and Col. Burr. New York. * ''William P. Ness vs. The People.'' January 1805. Duel papers, William P. Ness papers, New York Historical Society. * * Winfield, Charles H. (1874). ''History of the County of Hudson, New Jersey from Its Earliest Settlement to the Present Time''. New York: Kennard and Hay. Chapter 8,

Duels

" pp. 200–231.

External links

*– Official PBS Hamilton-Burr Duel Documentary site

Duel 2004

– A site dedicated to the 200th anniversary of the duel. {{DEFAULTSORT:Burr-Hamilton Duel 1804 in New Jersey 1804 in the United States 1935 sculptures Alexander Hamilton, Duel Dueling Monuments and memorials in New Jersey Political history of the United States Political violence in the United States Weehawken, New Jersey July 1804 events